by William Connery

April 20, 2018

My own experiences as a missionary actually began on December 23, 1974. I was working in Los Angeles for the last speech in the 1974 Day of Hope campaign for Rev. Moon. Another brother and I received forms to be filled out concerning the immanent Blessing. Although I was almost 26 and 3 1/2 years in the church, I felt unworthy for this great step. Still, I filled out the form, leaving everything in the hands of God. After Rev. Moon’s speech, I returned to Salt Lake City with the other brother. On January 7, 1975 we received word concerning the Blessing happening in Korea, but no other word was forthcoming. So on January 15 this other brother and myself took off to southwest Colorado for a fund-raising venture for the Center. I called the Center January 17 and was told by our director that the other brother and I would be going to Seoul for the Blessing! I was both shocked and grateful. The next day we returned to Salt Lake City and I applied for my passport on January 19, which was my 26th birthday.

We both went to San Francisco, where we spent a week fund-raising. All the American Blessing Candidates congregated in Los Angeles and arrived February 2 in Seoul. We were in Korea until February 10; the high point being the Mass Wedding of 1800 Couples on February 8, 1975. Then we all went on to Tokyo, where we worked on Rev. Moon’s Budokan Speech. Both Rev. Moon and Neil Salonen (president of the American Church) emphasized the importance of the 1800 Blessing for the work of world-wide restoration. We had a special meeting on February 12: a list of 95 nations was read out and we were to pick out 3. My choices were French Guyana, Rhodesia and Singapore. We left Tokyo February 15 and returned to the States. I traveled to Salt Lake City, where I worked until the end of the month. Then I went to training at Barrytown, New York (I also briefly stopped in Glen Burnie, MD. for a day to see my father and aunt — I knew it might be a long time before I would see them again). The training at Barrytown was quite an amazing experience. It lasted from March 3 until May 14 (at least for foreign missionary candidates — there were also 7 day, 21 day, 40 day and 120 day workshops taking place). During that period, Rev. Moon came to speak to us at least 10 times. His advice was always strong and fatherly (in one speech -¬ Directives to Foreign Missionaries – March 20 – he said:

Wherever you go throughout the whole world you will find established Christian churches. Do not try to fight or argue with that mission. Find a way to work together. Don’t argue, don’t make enemies. It takes too much time and energy. Tell them ‘you are my big brother or elder sister.’ Tell them ‘please pray for me.’ If you say, ‘The Principle is this, the Creation is like this, the Fall of Man is like this … Rev. Moon is the Lord of the Second Advent from Korea, etc.’ they will get upset! You don’t have to tell them all at once. Use your wisdom. Give them the precious jewel gradually … You can say Rev. Moon is a prophet — that’s fine.)

Most of our schedule during that period was very strenuous. We usually got up at 6:00, went outdoors for exercise, and had breakfast. Most of the day was spent listening to Mr. Sudo give lectures on Divine Principle and Spiritual Guidance. There were also three 30-hour street-preaching conditions during that time — two in New York City and one in Washington, D.C. The personal commitment of each missionary was being challenged. My own greatest challenge started on April 5. It was announced that some missions were going to be changed. One brother (Lorenzo Gastanaga), who was originally slated for Uganda, was switched to an American mission. And it was decided that no one would be sent to French Guyana, because it was still a French colony. Mr. Salonen took me aside and asked if I would be willing to go to Uganda. Without much hesitation, I said yes. Actually, I knew very little about Uganda but my information soon grew. I discovered that the nation was under the leadership of Idi Amin, and was considered one of the most dangerous countries in all of Africa. I gave my fate to God, praying in my mind: “Well, if You want to get rid of me, this is Your chance. Anyway, I will go because someone must bring Your New Word to the Ugandan people and it is better for me to die than for some worthier brother or sister to go and die.” God had guided me through many difficult situations in the past and I had trust in Him. Rev. Moon had wanted all the missionaries to leave for their nations by April 30. This could not be done, due to financial problems. On April 24 we had a big dinner at Barrytown as a send-off for 14 missionaries who were being sent out right away. The rest of us had fund-raising from April 25 until May 11.

On May 13 there was a farewell banquet for all foreign missionaries and the next day most of us visited the new National Headquarters which had just been acquired on 43rd Street in New York City. Then most of us left either that day or the next day for our nations. I almost didn’t leave America. I had two suitcases packed with books, tapes and clothes. I also had my sleeping bag. The airport personnel wanted me to leave behind the bag but they eventually let me go on board. I flew on KLM with a British sister who was going to Tanzania. We flew over the Atlantic on a Jumbo Jet: Elizabeth was in a section with over one hundred young people who were going to do Christian missionary work for six weeks in Germany. We switched to a smaller plane in Amsterdam and flew to Cairo, where we waited for 3 hours. No one was allowed to leave the plane except for those disembarking and also any taking of photos was forbidden; because the airport was considered a military installation (and actually soldiers with machine guns could clearly be seen from the windows of the plane). We took off and headed nearly due south. Elizabeth kept telling me to eat more food on the plane — my stomach was turning over like a person awaiting their execution. I arrived 9:30 P.M. at Entebbe Airport, which is twenty miles from the capital of Uganda, Kampala.

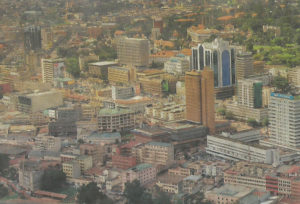

Rev. Moon told us to make special conditions for our nations. My first started as soon as I left the plane – I began a seven-day food fast. I felt that God was protecting me from the very beginning. The few people who were at the airport were either half-drunk or so fascinated to see a white person that I easily got through customs (I eventually found out that usually only three kinds of American white people come to Uganda: missionaries, CIA agents or crazy people — eventually I would be accused of being all three). It took me until 2:00 A.M. to get to Kampala and I began to experience the serious economic situation: the first taxi I took ran out of gas a mile outside Entebbe; luckily someone could stop and take us back and a VW van was found which took me in. The first few days were quite a memorable experience. I stayed in the hotel where the German missionary had stayed: he had come to Uganda on April 26 but had already moved, but nobody knew to where. The first day I went out to investigate my new surroundings. “Culture Shock” is probably a mild term which I could use to explain my first few days. Weather-wise there were very few problems. The weather in Uganda was very similar to the mid-May weather of New York. Even though Uganda is on the equator (Kampala itself is just thirty miles north of the equator) the altitude is 3000 – 4000 feet: during the day it gets no higher than 85° and during the night it drops to 60° and never lower. Two important aspects of living on the equator were very noticeable during my first year in Uganda. First, the sun always rises at 7:00 A.M. and sets at 7:00 P.M. – this was quite unusual for an American used to time variations in the sunset from 5:00 P.M. in the winter to 9:00 P.M. in the summer. Also summer, autumn, winter and spring – the change of seasons – had to be forgotten in Uganda. It was eternally springtime. And of course it was amazing to be around so many black people. I’m from Maryland myself, which had been a slave-owning state. I’ve never felt any hatred towards blacks (I had always been taught that we’re all human beings, equal in the sight of God), but I often felt uncomfortable around blacks because of the racial problems in America. Also most of the schools I had attended were all or predominately white and I had never developed any real friendships with blacks. So being in Uganda was being on a new planet, a completely different world from the one I had lived in for twenty-six years.

That first day I spent walking around Kampala. It is quite an interesting place. The original center of the city is built on seven hills (like Rome) and most of the hills are crowned by churches, mosques or hospitals. The center city itself looks fairly modern – with at least seven buildings that were 10 stories or higher (the two tallest were twenty stories) – but I soon discovered that looks could be deceiving. There had been no real development since 1972, the year that Amin had kicked out the Israeli technicians and the Asian merchants. There was a too-sudden attempt to Africanize the economic life of Uganda – Amin called it Economic War – but the ignorance of many people and the greed of others soon proved too harsh for the economy and a once-thriving nation was stopped dead in its tracks. I didn’t believe the mess I had read about in the magazines, but I saw living proof before my eyes in Kampala. Most shops had nice show-windows, but a quick step inside usually revealed practically empty shelves. The streets were full of people looking for “essential commodities” (a term I would become very familiar with) such as salt, sugar, soap, detergent – things that Americans take for granted but they were hard to come by in Uganda. The usual means for people to get these goods was through “magendo” – the black market — which even the government participated in: two pounds of sugar, officially about $.30, could usually only be bought for $1.20 – $1.50 — two pounds of baking flour, officially about $1.20, actually sold for $4.00 – $5.00.

In reality, the economic situation didn’t bother me too much in the beginning -¬ I was fasting for seven days and didn’t want to have anything to do with food.

My main concern was with people — how to reach them in order to teach them the Divine Principle (D.P.). That first day I met two people — Herbert, who worked at the Post Office and Oscar, a high-school student. Oscar told me someone had stolen his suitcase and he had no place to stay. So I brought him to the hotel and he stayed overnight in my room. The next day Oscar and I walked around, trying to find the German missionary. We also spoke to a few people and I treated him to two meals, though I continued my fast. My third day in Uganda was a Sunday. I woke Oscar up early and we both said the traditional 5:00 Sunday Pledge together. Later on we attended a service in the local Roman Catholic Church. In the afternoon the German missionary came to check on his mail and found Oscar and myself studying the Divine Principle in our room. I must admit that Ulf was grateful and shocked at meeting me. Grateful to know that at least one other missionary had made it into the country and shocked at all the material I had brought into the country — several D.P. books, a D.P. teaching outline, a tape recorder and over 30 tapes of Mr. Sudo’s lectures, spiritual guidance and some of Rev. Moon’s speeches. Even one of my bags still had a Unification Church sticker on it. Ulf quickly left: shortly afterwards Oscar and I went downstairs for tea and Oscar was almost arrested by an army man. It was my first contact with the local authorities: the man left us alone when he found out that I was a tourist-businessman and the young man was just trying to help me.

The next day Oscar left to return home — I gave him $10 which he said he needed for transport. Then I moved in with Ulf, who was staying at the local Scout headquarters. The woman there was friendly, but her boss did not want us to stay there; so Ulf and I moved into the cheapest hotel we could find for $8.00 a day. I returned to the Catholic Church and met Fr. Joseph, a white priest from Malta, who said I could see the local Vicar-General in a few days.

Both Ulf and I had entered Uganda on three-month tourist visas. We knew of the government persecution against the churches, especially newer and smaller ones, like the Seventh-Day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses. We knew we couldn’t operate openly as Unification missionaries. So we began the search to find the means to stay legally in Uganda. Ulf had about the equivalent of a Masters Degree in Engineering, so he began to search into businesses which could use engineering skills. I had a B.A. in History, so I decided to find a job as a teacher. (During our training it had been strongly stressed that we should stay in our nations as ginseng tea salesmen — but the government animosity against foreign business in Uganda was still so strong that Ulf and I decided to try other avenues closer to our own personal training). That is why I wanted to meet the Vicar General — possibly he could get me into the local Catholic school system. When I met him two days later he quickly closed the door on any contact with the Catholic schools. My main purpose in Uganda was to teach the Divine Principle and especially show people how it is a fulfillment of their own religious background. I come from a strong Roman Catholic tradition myself (including seven years in a minor seminary) and have always felt that the D.P. was the completion of my basic Christian faith. My own feeling was that God wanted to reach all people, and having a strong religious faith was sometimes a hindrance to God (just as when Jesus came – the people who accepted him and the Gospel were not the Pharisees and Sadducees but the fishermen, tax-collectors and harlots).

We were actually very blessed in Uganda. It had been a British protectorate for seventy years and English was the official language. And the better educated a person was, the more English they knew. So from the very beginning the people I met were very friendly and were honored to know a person who they could speak English with.

At the Roman Catholic Church I met Andrew, a student at Gaba National Seminary. On June 1 he took me to the Seminary, about twenty miles from Kampala. It is fairly modern, being run by local priests with help from the Verona Fathers. Andrew showed me around, I had some simple lunch with him and I was able to teach him some D.P. — he seemed interested and had a very inquisitive mind. I actually became a member of the choir in the Catholic Church and came to know most of the members: before the end of May I started teaching two of them D.P.

Meanwhile, our finances were being depleted by our $8.00 a day room and the need for eating (it was forbidden to prepare food in the room). Somehow Ulf met Abdul, who was a Bangladeshi working at a local college. Abdul was living by himself in a three-room apartment, renting it from the government for a nominal $10 a month. He offered Ulf and myself one of his rooms, which had its own entrance, for $40 a month. Of course he was making a profit — but he was still saving us money — one month in our hotel cost $240! So on the morning of May 27, Ulf and I moved in with Abdul; later that same day I visited Kibuli Mosque, which is on one of the hills overlooking Kampala.

On May 29 we began a seven-day condition of praying 3:00 – 4:00 in the morning. On June 3rd we had prayer 3:00 A.M., had some breakfast and then started walking to the Catholic Cathedral on Rubaga Hill. About half-way there we met a flood of people heading towards Namugongo, about eight miles east of Kampala. What were all these people doing on this day? On June 3, 1886, over 30 Anglican and Catholic converts had been burned to death for their faith at Namugongo by Kabaka Mwanga (the kabaka was the king of the local Baganda tribe). In 1964 the 22 Catholic martyrs were canonized by Pope Paul V1 and in 1969 Paul VI became the first Pope to visit Africa. He came to visit Uganda, where he dedicated the foundation for the Martyr’s Shrine at Namugongo. When he arrived in Uganda, Pope Paul VI had said: “At this blessed moment, for the first time in history, the successor of Peter as Vicar of Christ sets foot upon the soil of Africa. We give thanks to God for this great favour.” The Martyrs Shrine was not completed until 1975. Its official opening was on June 3 by the Pope’s Special Envoy, Sergio Cardinal Pignedoli, in the presence of President Idi Amin. Several hundred-thousand Christians gathered that day: we left early because the ceremonies were delayed due to the late arrival of Idi Amin. Still it was a stirring testimony to the deep faith and love of the people to be willing to walk eight miles (some had walked the whole night from longer distances). I had made an appointment to meet Oscar in Kampala, so I had to rush back to the city. I had missed my first opportunity of seeing Idi Amin.

On June 6, Ulf and I attended our second Balokoli meeting at the Anglican Cathedral on Namirembe Hill. The Balokoli (Luganda for “saved ones”) were still meeting every Friday evening, as they had since the Revivals first swept Uganda in the 1930’s. I soon discovered that they had a mixed effect on other people. Some ridiculed them because of their strict life style: no drinking, no dancing, short hair for men and women, no bell bottom pants; members would often start confessing their sins publicly in a crowded bus and ask people to accept Jesus in their lives. But when Ulf and I went there, we could see many brothers and sisters, some who were now elderly and had dedicated themselves to the Lord in the original ’30’s Revival, some who were young men and women who had decided to cast themselves completely on Jesus. There were also three older white women who attended: the meeting consisted of some members giving testimonies about their lives or asking for spiritual help and guidance from the brothers and sisters. Each person’s speaking was followed by the singing of the traditional ‘Takatendaraza’ (Praise the Lord).

During the month of June, I continued singing at the Catholic church on Sunday and attending the Protestant Revival meeting on Friday. On June 10 Ulf and I decided on three immediate goals: find our own accommodation; receive definite word about jobs; and witness to at least three people a day. Through the Friday Fellowship, I was able to meet Mr. K., headmaster of Nakasero Secondary School (N.S.S.)

I visited him on June 11; he offered me $40 a month to teach at his school (if I was accepted by his Board of Governors). Later that same day I met the headmaster of another school — he told me to return later in the week. Also on that day I met Mr. Singh, one of the last members of the Sikh society in Kampala.

On June 13 a11 meetings were canceled in the afternoon because President Amin was giving a speech in City Square Park. It was my first chance to see the most hated — and beloved — man in Uganda, depending on your tribe and whether your family had prospered under Amin’s “Economic War” of kicking out the Asian merchants or some member had been killed by Amin’s Security Forces.

It is worthwhile here to mention what Brother Andrew had written about Idi Amin in 1977:

The architect of this tragic new Uganda is a man who likes to be addressed as His Excellency A1.-Haji Field Marshall Dr. Idi Amin Dada, V.C., D.S.O., M.C., Life President of Uganda. To the rest of the world he is Big Daddy Amin. To many Americans and Europeans, he is a cartoon character – a joke. It is easy to laugh at him from the detached comfort of the Western World. But to Christians in Uganda, there is nothing funny about Idi Amin. … Like so much of the violence in Africa, the Ugandan persecutions spring partly from tribal rivalry. Amin’s small Kakwa tribe, known for its fierce, warring history, is a traditional enemy of the Acholi and Langi tribes, which include most of the country’s better educated business and professional leaders (including Dr. A. Milton Obote).

The Acholis and Langis are also predominantly Christian; the Kakwas, largely Muslim. … Amin has always been sensitive to his negative image in the world community, and has reacted violently to criticism of his regime.

And Godfrey Lule, the man who replaced Idi Amin in April 1979, wrote in 1977:

The system Amin has built up reflects his own background and peculiar talents. He comes from the far north-western part of Uganda. He is a member of the Kakwa tribe, which is based only in part in Uganda. There are Kakwa in far larger numbers in Zaire and in Southern Sudan. The basis of his power lies with the Southern Sudanese, who are recruited in large numbers to staff his police force and army. Many of these Southern Sudanese have lived in Uganda itself for several generations, forming a community known as Nubians. … (These people) have no interest in Uganda’s people or the future of the country. They owe personal loyalty only to Amin, a loyalty bought with imported luxury goods and the loot of their victims. They exercise a foreign tyranny more vicious than anything dreamed of by European imperialists or modern white minority governments in Africa.

Finally, Amin’s Minister of Health, Henry Kyemba, had this to write about his former boss:

Amin’s extraordinary sadism and cruelty have often been said to be a direct result of syphilis, which in its final stages affects the brain, driving the victim insane. Amin’s records show that he has indeed suffered from syphilis. … It is rumored that the disease is progressive in Amin and that he will eventually succumb to it. I have seen no medical evidence of this. But even if it is true, in my judgment it cannot explain his behavior. His extreme brutality is not the result of brain damage but a long-term phenomenon. His orders are premeditated and consistent. I have seen him dangerously angry. I have heard him lash out in apparently uncontrollable rage, ordering indiscriminate arrest and death. But he knows well enough how to stage-manage his rages. The most telling example of this occurred in mid-1973 when, for the benefit of a French television crew, he exploded in rage, threatening to shoot all recalcitrant ministers. He behaved like a wild animal. The tribal scars on his temple — the three vertical marks which have earned the Kakwa’s the nickname ‘One-Elevens’ — stood out sharply, as they always do when he is angry. Yet immediately after the television crew left, he joked about his performance. “How did it come out?” he asked me, laughing.

A librarian I had met at the Catholic Church, Mr. M., attended the speech and helped translate it for me. President Amin spoke mainly about forming a liberation army, to liberate Palestine from the Israelis and South Africa from the whites. (In other speeches, Amin had applauded the slaughter of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics; praised Hitler’s genocide of the Jews; and called for the extinction of Israel as a state. Amin is sometimes referred to as the Hitler of Africa and he wants to build a statue to the Nazi dictator). Most of the people cheered and applauded, especially where there were soldiers – I also noticed that some people on the fringes were snickering or sometimes trying to hide their laughter. During that speech and on many other occasions I heard many different opinions about Idi Amin. Some people considered him a great leader who had brought Uganda recognition on a world-wide scale. While I was in Uganda, he had himself proclaimed Field Marshall and people said he considered adding the title “Son of God” to his list – he himself is a Moslem, but he claimed that one of his relatives was a Catholic priest and the man who became head of the Anglican Church of Uganda, Sylvester Wani, is his uncle.

To other people he was a clown or buffoon – some members of his own tribe jokingly said that the V.C. and M.C. in his titles meant Very Confused and Mental Case (actually they mean Victoria Cross and Military Cross). But by the time I arrived in 1975, most people had grown sick of the bloodshed which kept Amin in power and were just praying for the day that there would be a “change in the wind.” Quite a few people said they would be willing to admit the British colonialists back into power – at least in those days there was a strict code of law and order. Nowadays anyone could just “disappear” at any time. The helplessness of Ulf and myself grew each day. As our circle of friends grew, more people told us stories of the beatings and killings that were taking place. Our hands were tied: if we did anything to help our friends we could be easily kicked out of the country. Our only solace was the word of God we could teach people through the Divine Principle.

I continued my desperate search to stay in Uganda as a high school teacher. I had never taught in any school before, but I’m always willing to try something new for the sake of God. But most of my contacts were dead-ends. I probably visited every high school in Kampala but with little luck. When I did have a lead, it usually resulted in a bureaucratic three-ring circus. Headmaster (A) usually said I couldn’t teach at his school unless I had a teaching permit from the Ministry of Education (B). The Ministry of Education refused to give me a Teacher’s Permit unless I gained a Work Permit from the Immigration Dept (C). Then the Immigration Dept. refused to give me a Work Permit unless I had a Teaching Permit and an official letter of recommendation from the school. I had to play this game several times in June and July, 1975.

My hope was to become a history teacher, since that had always been my favorite subject in school. But I had studied only United States and Western European History: my knowledge about Africa was next to nothing. So I made time to study African history, with a focus on East Africa and Uganda (one headmaster specifically turned me down because he believed I couldn’t learn and teach history at the same time). On June 24, the Ministry of Education rejected me for teaching in government schools. This only left the few private schools, of which N.S.S. was the most hopeful: June 25 I visited Mr. K. there and he promised to bring my case before the school Board of Governors.

The end of my first full month in Uganda was quite a momentous time for me. On June 30 I was able to finish the D.P. to one high school student, David S. And the next day, I was able to meet John-Patrick M. and his brother, David K.-M., who became two of our most faithful brothers. On July 2, I went searching for a young man I had met at the Catholic Church. Two other young men served as my guides as I went through a small village beyond Kibuli Mosque – they said I was extremely lucky because people were often killed around there “like chickens.”

On July 4 I began a Friday afternoon practice that was to continue for three years. Between 1:00 – 2:00 I visited Mr. M., the man who had translated for me during President Amin’s speech. I stayed in his office in his school’s library for 2½ hrs, sharing the D.P. with him. He was a married man with several children, and a lay-leader in the Catholic parish in a village outside Kampala. I left him about 4:30 in order to attend the Revival meeting at Namirembe. I would see many people come and go during my three years, but very few kept such an open, concerned and keen mind as Mr. M.

July 19 was the fourth anniversary of my joining the Unification Church. On that day something happened that Rev. Moon had spoken to us about on March 20, 1975. He had said:

A real father and mother are willing to risk their lives for their children. Are you ready to die for your children? If you reach that stage, you’ll love these people, even risking your life. Then you are standing on God’s side. … If you maintain the heavenly attitude, the spirit world will mobilize people, and show them to you in dreams. They will even come to you, saying ‘I saw you last night in my dream.’ ‘I saw you in a vision.’

On that day, Leonard, a young man I had been teaching D.P., visited me and excitedly told me that he had seen me in a dream and wanted to join the Unification Church! I remembered Rev. Moon’s words and felt God was working there.

On July 22 I visited N.S.S.: they were somehow losing two history teachers – I was hopeful that word on my appointment would be coming soon. I continued my daily schedule of prayer, history study, D.P. teaching, and visiting various schools and also many friends I had made by that time. On July 25 Ulf was able to get a three-month extension on his tourist visa. Little did we realize that the most serious test – to both our mission and our lives – was just around the corner.

July 27 began as a usual Sunday, with Ulf and myself holding 5 A.M. Children’s Pledge service (this we held ever Sunday and first day of the month, as is traditional with all U.C. members – luckily the apartment where we stayed was near a street lamp, so we never had to use our own lights and possibly attract attention from Abdul or any passers-by). Ulf left 9:45 for service at the Protestant All Saints church. I left 10:30 for mass at Christ the King Church. The two young men I usually spoke with were busy, so I met a new person, Charles, and we went to a small park near the City Hall. I began to teach him the Principle of Creation, which I had put on 3×5 index cards. While we were talking, a very flashily dressed young man walked by us once and quickly returned. He asked what we were doing, and I said we were studying how religion and science could be united. He asked for our I.D.’s, where I was living, and confiscated some letters I had been writing. He left us alone and I quickly returned to the apartment. Ulf was just finishing teaching Michael, a young man Ulf had met about two months before (Michael was a Christian, even though he was of the same tribe and actually a cousin of President Amin – he eventually became the first native member to stay with us). Michael quickly left and I told Ulf what had happened in the park.

We were still in the process of wondering what was the best course to take, when the young man came with two fellow members of the Security Forces. We were in the hands of the State Research Bureau (S.R.B.) Henry Kyemba has written:

The State Research Bureau – the secret police – was set up as a military intelligence agency to replace Obote’s bodyguard … they steal money from their victims; they are paid lavish funds by Amin as a reward for gathering information. … They do not wear uniforms. Typically, they dress flamboyantly in flowered shirts, bellbottomed trousers and dark glasses. … I have estimated the number of deaths over the past six years as 150,000 plus. This is well within the range of killings that Amin’s thugs could have achieved.

Abdul was also at the apartment and all three of us were arrested. All of our belongings were confiscated and we were put in the backseat of a vehicle. We were driven to what appeared to be a vacant house near All Saints Church. The driver went in for a few minutes, came back out and drove on. Next we were driven to the three-story building, which had the external appearance of a motel, where most of the S.R.B. victims were beaten and eventually killed. Our driver again went in and again he came out after a few minutes and drove us away. He continued driving us around until it got dark, in an attempt, we felt, of trying to confuse us. We were finally brought into a 10’x 12′ room which was located on the first floor of the S.R.B. living quarters. The three of us.were left alone for awhile; then they returned, frisked us, and accused us of working for the CIA – the first young man was sure I was with the CIA because I had a white shirt! – and we were plotting to overthrow the government.

All of Amin’s forces were hypersensitive during this period – the Organization of African Unity was meeting at Kampala during that same week – there had been some bomb threats against government installations: there was some method behind the madness of our being arrested. From the very beginning Ulf was demanding contact with the West German Embassy (there was nothing either Abdul or I could do — there was no Bangladesh Embassy and the American Embassy had closed down in November, 1973). Our captors kept telling us that everything had been taken care of. At one point, Ulf was ready to tell them that we were missionaries. But I said no, that we would keep our identities as tourists trying to stay in the country and also during our captivity, we would fast from all food. It was truly a life and death situation, with Ulf trying to teach the D.P. to Abdul, with both Ulf and myself trying to prepare our souls for whatever might happen (possibly expulsion or death), and all three of us trying to cope with our captors who came in once in a while to question us. Actually I felt that God was protecting us very much, because we were never physically abused by our captors. We spent Sunday evening and all of Monday locked up in our small room. Our captors brought food for Abdul on Monday; they seemed quite shocked that neither Ulf nor I were eating. Ulf mentioned to me early on Tuesday that we would probably be released with apologies. I had no idea what would happen. About 11:00 A.M. we were taken to the Crested Towers to check on someone, but they were not in (Crested Towers is the headquarters for the Ministry of Education). We were returned to the room, and then taken out again 1:30. We were driven back to our own apartment, where we could clean-up and shave. Then we were taken again to Crested Towers, where we met the Permanent Secretary for Education. He gave us our official government apology and hoped that nothing had happened to us. Ulf and I were grateful to God that we were unhurt and able to remain in the country. (We never figured out the full details of our arrest and release – any white men were suspect at that time, especially those having contact with the native people. Also we felt that Abdul’s being a lecturer at a local college was the reason that all three of us were released through the good grace of the Ministry of Education.)

Immediately after our release Ulf and I checked at the West German Embassy: they had never received any word about us! They told us to check all our belongings, submit a list of missing articles to them, and check with them at least every other day. We did get most of our belongings back, although most of our more valuable things and all of our foreign currency were gone. (Ulf’s had been in cash and was lost forever — mine was in traveler’s checks, which I eventually got refunded through a local bank). That Wednesday (July 30) I returned to my usual schedule of meeting with friends and attending choir rehearsal – no one seemed too curious about my absence. On Friday (Aug. 1) I went to N.S.S and met the headmaster: he promised to get my tourist visa extended. Later that day I attended the Revival Fellowship at Nambarembe, where I again met the headmaster and Sepia K., who was the actual owner of N.S.S. (The school had originally been an Asian school – Pilai’s – but it had been taken away from the Asians in 1972 as a result of the ‘Economic War’ and the Expulsion of the Asians). Later that evening Ulf and I saw Yasir Arafat pass us in a car.

On August 4 I revisited the Permanent Secretary at Crested Towers; he sent me over to the Chief Education Officer. He told me I needed a form from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The next day I got a Special Form from the Immigration Board. They then needed a copy of my University Diploma (luckily in our Barrytown Training we were told to bring a copy of any college diplomas we might have. Also another missionary in New York told us that we should keep 80 percent of our money in traveler’s checks). I recontacted the I. B. on Aug. 7 and I was at last granted a three-month extension on my tourist visa (Uganda was a place to learn patience – or else go crazy!).

On August 8 I met one of the great modern saints and eventual martyrs of Uganda, Archbishop Janani Luwum of the Anglican Church of Uganda (officially the Church of Uganda). He was attending the Friday Revival Fellowship at Namirembe. Brother Andrew said this about the Archbishop:

Luwum became a minister during the East African revival which swept Uganda before Amin came to power, and rose rapidly through the ranks of the church, becoming the archbishop in 1974 at a ceremony in Kampala’s Namirembe Cathedral. A photograph of the ceremony still hangs in the conference room of the Church of Uganda, showing Luwum … with a smiling Idi Amin offering congratulations.

But that was in earlier and better days. As the pattern of vio¬lence against Christians developed in the time since then, rela¬tionships between Amin and the country’s spiritual leader became increasingly strained. The plight of Luwum and other church leaders was a familiar one in countries where the Church is suffering: to speak out against the persecution was to incur greater hostility, and even personal danger to Luwum himself.

Although he was the Archbishop, I felt that Janani wanted himself to be treated like just another “brother in the Lord.”

August 10 I attended 11:00 Mass and sang in the choir. Afterwards one of the members, whom I had been teaching for two months, said that my presence was no longer needed in the choir. I felt immediately that people knew about my arrest and feared for their lives. I could not really blame them – still I felt hurt inside. Later that day I visited a friend and his family: I did not return to the apartment until 8:15 in the evening, really upsetting Ulf. Because of the desperation of the situation, I decided to make a 400-hour no-food fast (that is over 16 days without food). Before leaving America, someone had asked Rev. Moon — “Father, I was wondering if there are any special spiritual conditions which we can set in our country?” He had answered: “Fasting or some kind of a concentrated special prayer, in conjunction with deep concentration of your thought will be good. “There’s no necessarily uniform condition, but what¬ever individually feels good to you; there’s no right pattern.” Ulf decided to join me in this endeavor. The beginning was not too bad: I had accomplished three-day and seven-day fasts before. On the tenth day Ulf had to give up – he began passing blood in his stool. I kept on going, even though my energy level was decreasing and I felt like I had a fist of fire in my stomach. On Aug. 19 I went to N.B.S, and received a letter from the Immigration Board, requesting a teaching license and a letter of recommendation from the Permanent Secretary. I later visited him: he was away but his replacement seemed very responsive and ordered me to return with a copy of my diploma and a list of subjects I would like to teach. When I tried to sleep that night, my stomach felt like it was burning up. So I drank some water and prayed that God could give me some rest so I could do His Will. The next day I returned to the Crested Towers and the temporary Permanent Secretary wrote me a letter; he also said that if things did not work out at N.S.S., he would find me a place in another school.

I went to Immigration: they sent me back to Crested Towers because I still needed a teaching permit. I returned and received another form to be filled out by N.S.S. The following day I went to N.S.S. – the headmaster was late because he had been beaten and robbed the night before. He told me that he was leaving N.S.S. to work at Makerere University in Kampala (M.U.K.) and I should work with the owner from then on. On August 22 I received my teacher’s license and submitted all my papers to the Immigration Board – the man there said the I.B. would decide on my case within a week. Later that day Ulf told me that the Secret Police had visited the apartment twice. At 4:00 on August 28 I broke my fast (403 hours) with a cup of ginseng tea. September 1 I returned to the I.B. to check on my work permit. The man said it was still being processed and I should return in a week. I returned to the Immigration Board on September 8; they now said that my case would not be coming up until September 19. September 10 I visited Sepi K. at M.U.K.: he called the I.B. but still no definite response. On September 12 a policeman came to our apartment. He asked Abdu1 some questions. Then he asked me about my job and looked at my passport; he said it was a normal investigation and would return later to see Ulf.

A cold and sore throat had been working on me for a few days: on September 18 I began coughing up blood, so I went up to Mulago Hospital (formerly one of the best in East Africa — now fallen on hard times due to Amin’s regime). I was taken to a doctor, who gave me four kinds of pills and cough medicine. Later that day I met Ulf back at the apartment: he had been rejected by the Immigration Board and would have to leave by October 24. He started a three-day fast to set a condition. I met Sepi K. the next day: he seemed confident and gave me the name of the Chief Immigration Officer and told me to contact him in three days. On Sunday September 21 I visited a friend’s family in a village outside Kampala. His parents were very hospitable people, showing me around their shamba (farm) and preparing me lunch. When I left later they gave me a large bunch of matoke (plantains) and a hen. The next day I went to the I.B. and finally received my Work Permit, valid from September 10 1975 until September 9 1978! I quickly returned to the apartment and had a prayer of thanksgiving with Ulf; we were confident that through faith and prayer his situation would improve.

The next day began another chapter to test my toleration level. Now that I had a work permit, Ulf and I also felt confident that we could get our own accom¬modations. Thus began my relationship with the Departed Asian Custodian Board (D.A.C.B.), which was in charge of all the property which the Asians had been forced to leave behind after their expulsion in 1972. By 1975 there was no new building in Kampala and the population continued to increase. Some of the young men I visited were living in rooms that had formerly been servants quarters; sometimes whole families were living in converted garages. On September 23 I first contacted the D.A.C.B, and went there at least two or three times a week until they found me an apartment in March, 1976.

I had my first day at N.S.S. September 25. I sat in on a few classes and spoke to the headmaster; he needed two photos and two copies of my work permit. Also sat in on classes the next day and received my first pay-check ($200 a month). On September 26 we established the first Holy Ground on Old Kampala Hill (by this time Ulf and I had discovered Hideaki, the Japanese U.C, missionary who had entered Uganda on May 26 – I had seen Hideaki on the street before our formal introduction). On September 29 1 taught my first history classes – I felt like a prisoner awaiting execution. Somehow I (and the students) survived that first day. I also volunteered my services to help direct the school’s Bible Society.

October 9 was the celebration of Uganda’s thirteenth year of independence. Hideaki and I invited some of our friends to see “Diamonds Are Forever” at one of the local theatres — there are five cinemas in Kampala, plus one drive-in on the outskirts. We usually went to the movies about once a month: most of them were Hong Kong Kung-Fu specials and Spaghetti Westerns, though some high quality films were pre¬sented once in a while.

On Oct. 21 our first Holy Ground was destroyed and we moved it a short distance to a small (now vacant) building which had served as the first Uganda Museum. Every day for many months I went to that spot and prayed, overlooking the whole city. About this time final exams were starting at N.S.S.: I was lucky that the Uganda school system began in January and not September – this gave me more time to study my African history. And on October 26, under the direction of one of my students, I visited the Gospel Assembly Church, which had been established by an American in 1963; by 1975 it was a locally run institution.

On November 3 (Children’s Day), Ulf and I went to Jinja, 40 miles east of Kampala. Jinja is the second largest city in Uganda; it is also the industrial center and home of the Owens Falls Dam, which is the main producer of hydroelectric power in Uganda. But Jinja is most importantly the Source of the Nile River; the actual place where that River begins from Lake Victoria and starts on its 4,000 mile journey through Uganda, Sudan and Egypt. Unlike many rivers, which start from small creeks or from the run-offs of mountain snows, the Nile is a full-fledged river from its very beginning. We also visited the spot across from which John Speke had been the first white man to see the Source in 1862.

November 6 was the start of the East African Certificate of Education Exams (E.A.C.E.). The school system in Uganda is composed of seven years of Primary Education, four years of ordinary-level high school (0-level), two years of advanced-level high school (A-level) and three years of University at the only University in Uganda, Makerere. A student did not get a diploma simply by graduating from a school: he or she had to take special exams which tested their accumulated knowledge. Where I was teaching was a four-year ordinary-level high school and a11 of November was devoted to the fourth year students taking their E.A.C.E. exams. I proctored some of the exams, while I also corrected the exams I had given to the lower classes. Our school was co-ed, with students usually between 13 and 18 years old. The students were there for various reasons: some had too¬-low scores to enter government schools; some were the children of ‘nouveau riche’ parents (mafuta mingi in Swahili) who either wanted their children to get the education they never received or to get the kids out of the house; and some

people were actually interested in education! Space was another problem; my smallest class had 40 pupils – one of my classes had 80! And of course discipline was a problem – growing up in the ruthless environment of Amin’s regime had hardened some of them and I was forced to strike a few students. But I do have to admit that the majority of my students were attentive and responsible young men and women: I hope to be able to meet them again some day.

November 8, 1975 was a day of trial and testing for both U1f and myself. Oscar, the high school boy whom I had met on my first day in Kampala, came to pay me a visit. He had visited me intermittently since May 15, but he was always requesting money from me, even though I always focused our meetings on the study of Divine Principle and the Bible. He showed his true colors on this day, threatening to turn both Ulf and myself over to the police unless he was given a bribe. I pleaded with him and reminded him that any turn against us would involve himself. I finally gave him $15 and he promised never to see us again -¬ and actually I never did see him after that day. Later that day, Gaquandi, a young man from Zaire whom Ulf had met, also came. He began talking all kinds of nonsense and seemed either mentally unbalanced or spiritually possessed. When he refused to leave, Ulf called the police. When the police came, Gaquandi told them how he was involved with us in a gold-smuggling scheme. We told the police his situation and said they could search our apartment if they liked. Somehow they trusted us and took Gaquandi away. Ulf and I were thankful and grateful that we could keep our positions in the nation: also we were angry to see how Satan used people, especially in relation to money.

Ulf -was able to submit his papers for a work permit on November 18. He had tried using his engineering skills to get a job at various places, including a car-repair agency, the University, and even UNESCO. He finally could get a position with Dr. A. who ran a firm of consulting engineers right across the street from the West German Embassy. His office was in the same building with the South Korean Embassy (which had been the Israeli Embassy). Ulf could establish good friendship with both embassies. December l was Ulf’s first full day at his job.

On December 8 I received a ration card from Fresh Foods, Ltd. As I have mentioned, it was very difficult to get what we consider the bare essentials of life (salt, sugar, soap, cooking oil). Ulf and I had been sharing some of the commodities that Abdul could get with his card. And every once in a while we got lucky and happened to be at a shop when sugar or baking flour would be distributed. But you had to be quick – once put on sale, most essential commodities would be sold out in an hour or less.

Ulf returned to the Immigration Board on December 15 and discovered that his appli¬cation for a work permit had been turned down. He brought his case to the West German Ambassador: he met with the Minister of Internal Affairs on December 22. The next day found Ulf overjoyed: he had received a work permit good for two years.

1976

School had ended for me on November 28 and the new year began December 29. Both Ulf and I were now seriously looking for our own place. We had also been informed that after six months we should seek separate dwellings or even go to a different city. Ulf and I just kept pestering housing organizations; the D.A.C.B., National Housing Corp. (N.H.C.), the Uganda Muslim Supreme Council (U.M.S.C.) and others. I was promised many apartments – usually they were occupied by the time I got to them. On January 22, I was given an apartment – it looked like a disaster area. But while I waited for it to be painted, someone else had put their padlock on it and had broken mine off. On February 2 I discovered three men at “my” apartment – ¬one of them claimed to be an army sergeant. We all went to the D.A.C.B. – the Housing Officer had not been informed of my moving in so the army man had been given papers and moved in. Everyone agreed that he had no right to be there, but he refused to move until given another accommodation. I could make friends with the Lieutenant in charge of security at the D.A.C.B. and he tried to help me on my case. Various people dilly-dallied on my case for over two weeks – it was not settled until March 2 when it was decided that a Captain would be placed in the apartment, the sergeant would be kicked out, and I would be promised another place!

Finally on March 15 I moved into a small apartment just a block from the school. Shortly afterwards Ulf could also move into an apartment near the open-¬air market. On March 28 Ulf could borrow his bosses VW bug and seven of us piled in. First we drove east to Jinja and established a Holy Ground near the source of the Nile. Then we went through Kampala and south to Entebbe, where we established a Holy Ground near Entebbe Airport. March 31 we celebrated the first church holiday at our own place (my apartment). We established a tradition which we generally followed in the future: food preparation in the morning (after 7:00 Pledge Service); a feast about noon; games, singing or testimonies in the afternoon; and going to a movie in the evening.

On April 4 I attended the Gospel Church; I had already visited there a number of times, had sung some songs and given testimony. Now they asked me to give a sermon on April 25. The next day my new neighbor, Mr. Y., promised to make blackboards for me (he was in charge of a large bookstore in Kampala). A few days later John-Patrick could move into the apartment with me: about the same time Michael moved in with Ulf. On April 19 John-Patrick took me to Kasubi (a few miles outside Kampala) to visit the Kabakas’ Tombs: Kabakas Mutesa I, Muranga, Daudi-Chwa and Mutesa II are all buried in a native-style mausoleum.

April 20 we received a message about a visitor coming from New York City. And April 23 he had arrived. It was Mr. Song; he was one of Rev. Moon’s earliest disciples – he had joined when he was 12 and had been a member for 25 years. His visit was a real revival and a breath of fresh air. I met him near my apart¬ment and walked him over to see Ulf; on the way he bought many fruits and vegetables. John-Patrick and I had just finished a three-day fast while Ulf, Hideaki and Michael were starting one. Mr. Song told us to forget about fasting – we needed to eat so that we could work harder. He said that we should not be separated: since Ulf had the largest apartment, Mr. Song said we should all stay together there. So I quickly moved out of my place and Hideaki made plans to move away from the lecturer he had been staying with at the University. Mr. Song told us about the situations in other African missions – some nations he had been unable to enter and others he had only stayed three hours or one day. He could stay with us almost five days. During that time I gave my sermon at the Gospel Church. He also bought us much food and took us to the movies several times. We felt revived, refreshed and renewed by the time he left.

On May 2 we switched our Holy Ground from Old Kampala Hill to Namirembe Hill, near the cathedral. And May 4th I attended my first meeting of the Kampala Businessmen’s Lunch Meeting at the Speke Hotel: Archbishop Luwum was the guest speaker; his topic focused on a recent Anglican Conference held in Trinidad. I had been introduced to this group by Mr. K., a former seminarian whom I had first met in January and had met many times since, speaking about religion and other topics. He had studied in England and was now an asst. manager in an insurance firm. Thus began one of my most fruitful contacts in Uganda — I attended that Tuesday meeting from then on, meeting many of the Christian leaders of Uganda; eventually Ulf, Hideaki and I could speak there several times over the next two years. Also what was left of the British community usually attended the Tuesday luncheons; through this I started attending Bible Study at one of the homes of an expatriate. May 29 we celebrated Day of All Things by driving up to the Baha’i Temple, about a mile from downtown Kampala. The Baha’i faith has a temple located on each continent: so this Kampala Temple was the Baha’i center for all of Africa. It is located on top of a hill, with flower gardens and manicured lawns. We had a prayer inside and also visited the Visitor’s Center. And this year we took a taxi to attend services at the Namugongo Martyr’s Shrine on June 3. (I had written down the names of the twenty-two Catholic martyrs and reminded them daily to help their physical and spiritual descendants give their support to the modern dispensation).

On June 11 we heard about an assassination attempt on Idi Amin. (He had been attending a police review. He left early, driving away with his own driver in the passengers’ seat. Two grenades were thrown at his vehicle, exploding next to it and behind it. One seriously wounded his driver, who died two days later. Amin had amazing luck – or premonition – at this and other times – if he had been where he was meant to be he would be dead.76) The next day we began going through any of our belongings that could be used against us if we were arrested again. On June 26 Amin had himself declared “Life President” (or as one friend of ours said “President until he dies”). An event of international proportions began on June 28. An Air France jet had been hijacked from Lebanon and flown to Entebbe Airport. Idi Amin immediately stepped in as a “neutral negotiator” -¬ although everyone knew of Amin’s hatred of the Jews and his support for the Palestinian guerillas – the hijackers had Palestinian connections while eighty passengers were Israelis. On July 4 we heard of the daring Israeli Raid on Entebbe – although-people had to publicly condemn the raid, most of our friends admired the courage and forcefulness shown by the Israelis and how President Amin had been made to look like a fool. July 6 and 7 were public holidays to mourn for the twenty-three Ugandans and seven hijackers killed in the raid. July 22 I -was stopped about two blocks from school by two secret police. They asked what I was doing and what was in my bag. I said I was a teacher and my bag contained books. They had a look and quickly left.

Hideaki had been able to start classes at the University on July 1. He had been able to overcome the language problems and been able to stay in Uganda on his wits and the grace of God. Because of his experience as a center leader in Japan, he was the unofficial central figure, even though my own thoughts were that the three of us were equals and each one had something important to contri¬bute. (Someone had asked Rev. Moon during training “I’d like to know if there are special roles for Germans, Japanese and Americans. For example, Cain-Abel, Adam & Eve, etc.?” He replied: “Father does not think that way. The application of the Cain-Abel relationship is often misused or misinterpreted. There is no Cain and Abel. ‘You are three brothers and sisters. Natural leaders periodically emerge, of course. Then you pray centering on Father, and everything is going to be O.K.”)

On Aug. 24 John-Patrick returned from Nairobi where he had been working since the beginning of May. Many pages could be written about the people Ulf, Hideaki and I met over the three or more years we spent in Uganda. Some were seekers after God and moved into our center for various periods of time. Some just saw us as rich white men (for many people white = rich). After being “burned” a few times during our first months, we established a strict policy of no financial or physical hand-outs. We often had to make difficult decisions and constantly prayed that God would guide us in the proper care of our new members. September 4th found Hideaki and me at the University, listening to an ecumenical talk. Dr. A. Lugira (who later fled the country with his family) spoke on “Aspects of Prayer and Worship”; his main point was that things went slowly between churches because of lack of approval from the higher centers.

Letters were always an important part of our lives. Especially we were trying to keep abreast of the Yankee Stadium rally in June 1976 and the Washington Monument rally of September 18, 1976, which was the second anniversary of Rev. Moon’s first major breakthrough at Madison Square Garden. Finally on September 28 we re¬ceived word (from Japan) that W.M. had been a great success. It was also during this time that Rev. Moon’s picture appeared on the cover of the international Newsweek magazine. Somehow we received five copies through the mail; it broke our hearts but we had to destroy them by fire in order to keep our cover.

Our relationship with the foreign community was strange and interesting. This was due to our own position and most of the foreigners in Uganda were strange and interesting. I don’t mean this in a bad sense. Especially if you were British or American you had to be dedicated to stay. But everyone had to walk a tightrope (we knew of one West German who came to teach in a local college — he took pic¬tures all over the place – got picked up and beaten by the Secret Police and left Uganda within a week.) One American couple came during the Entebbe Crisis – and left after he finished a year of teaching chemistry at the University. I usually met foreigners when I went shopping; this included Russians, Red Chinese and North Koreans – all of whom I avoided as much as possible. I’m glad that God had given Ulf, Hideaki and I enough common sense to pick our friends carefully and keep our mission foremost in our mind.

The first week of November, 1976, was devoted to an Ecumenical Revival at the University. We heard Bishop Festo Kivengere, an internationally known Ugandan Evangelist speak. Archbishop Luwum also spoke at that time. There was even a film — Billy Graham expounding on the Ten Commandments (many of the students were angry because the film had been billed simply as “The Ten Commandments” and were expecting the epic with Charlton Hesston.) November 13 was closing ceremonies, with speeches from the Greek Orthodox Bishop, the Anglican Archbishop and the Catholic Cardinal. One of our friends -was a teacher at a local grammar school. On Nov. 24 I could speak to his 7th grade class on the Purpose of Life and the Process of Creation. The children were very responsive and I was hoping that this would lead to a new avenue in our work. But my friend visited me five days later and said I couldn’t speak there again – he had probably gotten some bad reactions, either from other members of his faculty or possibly from the Secret Police. At least on December 12 I was able to speak again at the Gospel Church.

My first full year of school ended November 30. December I spent studying, teaching the Divine Principle to our friends and attending the Tuesday Luncheons. We could attend a Christmas party at one of the British homes (complete with a little fake snow, made out of cotton) and had a Christmas party for our friends on December 25. January lst we celebrated God’s Day. I started teaching again on the 10th. Ulf also could take his first “vacation” (Dec. 31 – Jan. 16). John-Patrick suddenly returned on February 8. He had gotten a job as a steward on East African Airlines. But the Airlines was now defunct due to the breakdown in relations between Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania.

1977

Another major crisis started on February 14. It was announced on the radio that Archbishop Luwum was implicated in a plot to overthrow the government. On February 16 a statement was read, reportedly written by Milton Obote, concerning the overthrow of Amin’s government.

Archbishop Luwum and two cabinet ministers had been arrested. The next day Hideaki told me the news about the “car accident” in which a11 three men had been killed, even though their driver had been only slightly injured.

(The truth was reported in Christianity Today (March 18, 1977) :

Amin ordered all three shot and the two government officials were promptly killed. When the president learned that his troops were reluctant to shoot the archbishop he is reported to have shot Luwum himself. Soldiers were also reported to have been reluctant to follow Amin’s order to run trucks over the bodies of the three; they finally agreed to crush the corpses of the cabinet ministers but not the archbishop’s.

We all felt deep sorrow at the loss of our brother and dear friend – a modern Uganda Martyr.

February 19 we moved to a new home, a three-bedroom house close to the University. Ulf had been able to rent the place through one of his business contacts. On February 25 there was a radio announcement requesting that all Americans were to meet with President Amin on the following Monday, February 28. His Excellency said he wanted to make awards to the Americans who were devoting themselves to Uganda (we weren’t sure if they were going to be .38 or .45 rewards!) February 27 it was announced that he President’s meeting was being postponed until March 2 and was being shifted to Entebbe: later that day there was news of American forces being landed in Mombasa, Kenya. Finally February 28 there was news that the meeting with the Americans was being indefinitely postponed because of March 2 being Mohammed’s birthday (later one of my friends in the telephone bureau told me that President Carter had actually called Idi Amin and told him to leave the Americans alone).

We were able to stay in our new house for over a year. During that time four of our Ugandan brothers were able to stay with us. Our daily and weekly schedules became more solidified, with prayer meetings at the beginning and end of each day: lectures usually two or three evenings a week on Divine Principle, Unification Thought and Victory Over Communism. And Sunday we had our 5 A.M. Pledge service, a (more or less) public service at 10:30 A.M. and a Sunday afternoon D.P. lecture after lunch. All these services were on a rotational system: especially we wanted to train our native members because we were never absolutely sure of our position.

On April 22 we had a robbery attempt at our new house. (Someone had actually robbed our other apartment shortly after Mr. Song had visited us). Hideaki had been home and gone out 11:00 to do some shopping. He returned within an hour, to find the main door of the house broken in and a man waiting inside. The man quickly excused himself, saying he had just stepped in because he saw the robbery taking place. He went back out the door, whistled (probably to warn his accomplices) and ran away. Hideaki found that our radio and other valuables were neatly tied in bundles – we actually were only missing a clock and some cash. Shortly afterwards we hired an askari (guard) to take care of the house during the day while we were at work or school.

Hideaki’s academic year also ended in April and the University refused to renew his application: he had been attending the school under a “special student” status. During May he came with me to N.S.S. and began teaching Math in the afternoon; shortly afterwards he had to stop because the Ministry of Education refused to give him a teaching permit – he had no University degree. After that he could get his entry permit extended for three-month periods at a time while trying to open an import-export company.

May 26 we established a new Holy Ground on Kololo Hill, which is the highest hill in Kampala, about two miles from the center of the city. We had established our Holy Ground on Namirembe Hill where we thought it would be safe. But there had been some sort of Archdiocesan meeting where it was decided that a new congre¬gation hall was needed: and the only place suitable for it was where we had placed our Holy Ground! Our new Holy Ground we felt would be safe: it was near a house used by the Secret Police (and later we were almost arrested when we went up there to pray: luckily one of our members (the President’s cousin) could speak their language and they just let us go).

Two important national events happened at the end of June. On the 29th President Amin conferred on himself the title “Conqueror of the British Empire in General and Africa in Particular” (C.B.E.), another ridiculous boost to his ego. The next day was the 100th anniversary (Centenary) of the arrival of the first Christian missionaries in Uganda – there was a large ceremony at Namirembe Cathedral with the President attending.

Also at the end of June I was elected Chairman of the Scripture Union at school. Up to that point I had not done too much concerning religion at school. But now I was in charge of the weekly meetings. Eventually I tried to split the meetings: half the time the speaker would be from the Anglican or Catholic Church; the other half they would come from our native members or Ulf, Hideaki and me. The meetings were not compulsory and anywhere from 2 to 30 students attended at various times.

On September 21 there was news in the paper about all religious sects being banned except for the Muslims, Catholics, Anglicans and Greek Orthodox. Even the Baha’i Temple was to be shut down. We were glad that we were not a recognized “religious sect” so we could not be shut down!

When I attended the Tuesday Luncheon Fellowship on October 11 I met Dr. R., one of the few remaining Professors at the University – earlier that day I had met his brother-in-law at N.S.S. Dr. R. had received his doctorate in America and one of his children had even been born in the U.S.A. He was a scholar yet a true African: warm-hearted, generous and a brother in the Lord. At least once a week, from then on, I would visit him, his wife and darling four children. October 18 was an exciting day at school. Students were preparing for the final exams and one teacher discovered that a student had his final Biology exam – he discovered that another student had the Literature, Physics and Math finals. The school typist was implicated – he had been selling copies of the exams to the students for $5. The typist was fired and we were to keep our eyes open for too high scores – it was too late to redo the exams. About the same time Hideaki was knocked off a bicycle by a Mercedes car – he sprained his foot yet still kept working – he could also receive a special entry permit and business registration. Also I began to teach some Muslim students in N.S.S. from Rwanda – they were a mixture of Omani and African blood. I myself had been reading the Holy Koran that year and felt real hope in reaching Muslims, presenting D.P. as a new revelation and Rev. Moon as a modern prophet.

In December we were taught a hard lesson by one of our best home members. He came to visit in the morning. One of our native members was home and let him listen to some lecture tapes while he continued washing clothes. About an hour later he came back to the room, to find our tape recorder missing. Some time later we had to have one of our members leave the house because we found him stealing some essential commodities in his trunk. This member later repented and continued to visit us, although he couldn’t move back in. Various members, we discovered, had girl friends or dabbled in the black market. It was extremely difficult keeping a high moral standard yet knowing the chaotic environment of Uganda.

1978

In January I started my third full year of school on the 16th. During the previous year, besides being Scripture Union Chairman, I was head of the History Department (two of us), and Senior Study Master (a position similar to asst. headmaster). I was also secretary for staff meetings and in charge of distri¬buting paper and pens to the other teachers. Eventually I even got my own small office.

February was quite a momentous month for a11 three of us. The owner of our house suddenly stopped by on the 5th and announced that he had sold the house and we would have to move out by March lst. Just as we were beginning to contact our friends and the various housing agencies, we received word on the llth that we should be in Kinshasa, Zaire as soon as possible. Lady Dr. Kim, an early follower of Rev. Moon, was visiting various regions in Africa. We were actually supposed to meet her in Nairobi at the beginning of February, but we had gotten the message too late. We left on the 16th, after getting tickets and the necessary documents to leave and return. We spent almost a week in Kinshasa, with missionaries from five or six nations. Also the center there had 30 or 40 members and they were in the process of being recognized by the government.

Dr. Kim spoke to everyone together several times and saw each person individually. She thanked everyone for their hard work and sacrifice during the three years. It was a time of revival and renewal for all of us. We were back in Kampala late on the 22nd.

March 1 came and went without us being kicked out of the house. Our search for a new dwelling continued. It seemed that either no one knew of any vacancies anywhere or people would tell us of vacant houses – that had been occupied the day before. On the 19th we started a seven-minute nightly prayer for housing.

During March and April I had a breakthrough at a local high school. It was the school where I had been visiting the librarian almost every week for the past 2 years. On March 30 he told me that I could speak to about 100 students the following week on the Principle of Creation. April 6th I spoke for over an hour and answered questions from between 80 and 100 students; they were very curious and open-minded. April 20th I returned for a final lecture on the Purpose of Life and the Fall of Man. My lecture series ended there and in some ways I was glad: the price of fame in Uganda was usually fatal.

At the end of March we had contacted the Church of Uganda at Namirembe – ¬they owned some housing but none of it was available. April we continued searching and in the first week of May we could get an empty apartment near Namirembe. We rented a truck, loaded it up and moved to our new home, a small, two-bedroom apartment (about half the size of our house). Also ever since our trip to Kinshasa (or even before), we had often spoken about touring the country. Ulf had gone several times to Nairobi and had gone to different parts of the nation for his engineering firm. But except for brief trips to Entebbe and Jinja, Hideaki and I had never seen the rest of the country. We contacted several travel agencies and finally settled on one. Hideaki and I tried to leave on the 15th, but there were no vehicles available (it -was also my third anniversary in Uganda). We made connections the next day and headed north from Kampala. The area around Kampala is hilly; as we traveled north the land became flatter and more arid. At 1:30 P.M. we arrived at Paraa Lodge, not far from the Kabalega (Murchison) Falls, the largest falls on the Nile. The operators wanted to charge us $85 for a boat trip on the Nile, but we refused. About 4:00 we recrossed the Nile in our van and the driver took us up the back way to the Falls. (The Falls are actually only 20 feet across and 130 feet high; but the whole pent up volume of the river dashes out of a ravine – it is more of an explosion of water than a fall). It was truly a powerful, inspiring sight. On the way back to the Lodge we outran a storm and saw a beautiful rainbow. The next day we visited another place along the Nile (Chobe Lodge). In the afternoon we went on a game ride and saw giraffe, hartebeest, warthog, waterbuck, and a herd of elephants. The lodge is famous for its baboons which will even come into rooms and steal things if windows are left open. We saw them and Hideaki wanted to become friendly with them – one man warned us that they were known to bite through a rifle!

The next morning Hideaki and I tried our hands at fishing in the Nile; we were near a pool of hippos. One of our guides caught a perch; Hideaki and I struck out. Our driver took us to Lira, a small town nearby. Hideaki and I wanted to see the eastern part of the country, but we felt it could be too expensive to use our van and driver. We used public transport from then on. We stayed overnight at the Lira Hotel. The next day we traveled down to Mbale, the largest town in eastern Uganda. It is reputed to be the most beautiful town in the country, at the foot of Mt. Elgon, which is 11,000 feet high. We just stayed overnight there and returned to Kampala the next day. We could see why Uganda was nicknamed “Pearl of Africa.” Once the political climate improved, Uganda could become a tourist Mecca, due to the mild climate, game parks and magnificent scenery.

During this time the first International 40-day training session took place at the New Yorker Hotel. 41 nations were represented, including Uganda. John-Patrick, whom I had met three years before in the Post Office, had been able to sneak out of the country (he still had a passport from his previous job in East African Airways -¬ he hid it when he crossed the border into Kenya). Two months later he returned to Uganda on the train. He could bring many books and tapes back with him – there was no border check and he took his things off in Jinja, before they could be checked in Kampala!

We gradually settled into our new home in May and June. June 6 we could celebrate Creation Day there. June 13 I was appointed treasurer of the Tuesday Luncheon. I began visiting more people at the University, including Dr. R. and Dr. 0hin, a West African surgeon who had spent over 15 years in America.

August was a busy month for us. Ulf was able to get both a printing machine and an electric typewriter. I was able to get my work permit extended until August, 1981. Ulf, Hideaki and I had been discussing for some time what type of business could support the church in the future. A friend of ours at the University said we could get land from the government about 80 miles west of Kampala. We were considering raising cows and opening a cheese factory. I began writing and drafting letters, especially to cheese-making companies in West Germany. There were also various reports and rumors about a talking tortoise and a cow giving birth to a baby boy. And August 15 was the second time I had seen a news article about Rev. Moon in the local English paper (Voice of Uganda): it dealt with the New York newspaper strike and News World being the only paper published (the first article had appeared when the church had bought the New Yorker Hotel.)

September 9 was the third anniversary of my work permit. On that day Hideaki and I went to Namirembe Cathedral, where we met Bishop Watanabe, visiting from Hokkaido. Later that day the sister-in-law of my school’s owner was married, also at Namirembe. About 6:10 I was back in our apartment and I received a phone call. It was Nancy Neiland calling me from Church Headquarters in New York City! She told me that “Your Dad wants you to come to the Seminary” – in other words, Rev. Moon wanted me to start a new mission as a student at the Unification Theological Seminary! I was truly shocked – I had never applied to the Seminary and never thought I would ever go there. Ulf, Hideaki and I had a good cry together – we were glad at my good fortune of being picked for the Seminary and sad about my having to leave the mission-field. The next day we went to Entebbe, where we prayed at the Holy Ground, visited the Botanical Gardens and had lunch at Lake Victoria Hotel. Before returning to the apartment, we visited the Namugongo Shrine, the Baha’i Temple and the Kabakas’ Tombs. The next morning we discovered that an Air France flight for Paris, which usually only came through on Thursday and Saturday, was coming through that very evening. We could get a ticket and take care of legal matters for leaving the country -¬ I told everyone that my father had died and I had to leave suddenly in order to attend his funeral. Ulf and Hideaki later that day took me to Entebbe, where we had a final prayer and cup of tea and I left 8:40 P.M., vowing, like General MacArthur that “I shall return.”

Postscript and Conclusion